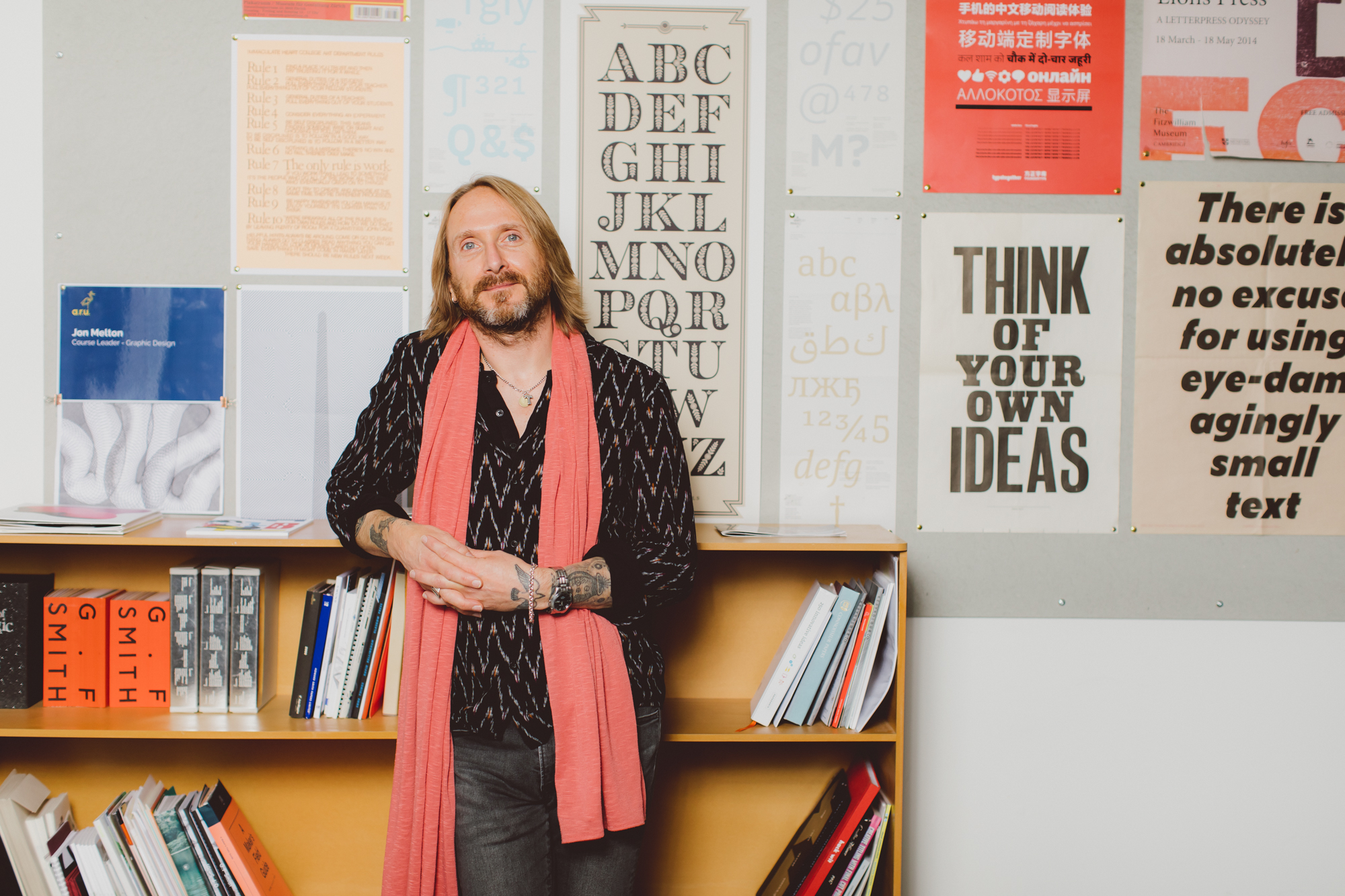

Nick Jeeves

Staff. Graphic Designer

As well as teaching Graphic Design, Nick Jeeves produces books as editor for the Ruskin Arts Publications and The Public Domain Review. He also publishes small editions of original writing and revived historical texts through his own imprint Mulita Small Editions.

What are you most interested in when it comes to publishing?

My abiding interest is in works of the imagination in text and image. Right now, that means working on a collaborative project between students at Cambridge School of Art and Di Tella University in Buenos Aires, making images inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ ‘Book of Imaginary Beings’.

What one thing (piece of art, writing, design, music, historical event etc) inspired you to do what you do now?

It’s really a slow accumulation of things, objects and experiences that have gathered into something bigger. I would say that books obsessed me from a very young age. I was attracted to how they looked and felt, as much as how they read. And I liked that they could simultaneously comfort and challenge you.

At some point I would have found out that books were put together by graphic designers, and from then on, that’s what I wanted to do. But realising that was by no means a linear process. I was distracted by any number of ideas along the way, and that’s still the case today.

I could quite honestly say that my work is inspired as much by musicians like Charles Mingus or The Grateful Dead, or by writers like Clive James or Fred Vargas, as it is by designers like Corita Kent or Barney Bubbles. Inspiration comes from how you connect your various enthusiasms.

But if I had to pick one key artefact from the distant past, it would be my Penguin copy of Evelyn Waugh’s ’Decline and Fall’. I read it at 14 and fell for it completely. It was my introduction to so many important things: how it read (a beautifully clear prose style, funny, a bit transgressive); and how it looked (immaculate typesetting, perfectly formatted, a striking cover design). It’s a book that raised me up.

What’s the most valuable thing you took away from education?

School was sometimes difficult as the education system, at that time, hardly valued the arts at all. In some ways that suited me as they became a private pleasure. That changed when I did my foundation course at the now defunct Shephalbury College in Stevenage.

Shephalbury was a world unto itself — just the right side of anarchic, and a place in which all the tutors were practitioners. Each of them was amazingly passionate and charismatic, but also very kind, in a no-nonsense sort of way. I’d never met a group of people like that before and it was totally liberating for me. We weren’t taught the subject as such: instead we were taught how to educate ourselves, and each other. It was learning by doing, and by sharing.

A meaningful arts education asks you to bring your own interests with you, and expects you to pursue them and discuss them in the context of the set projects. Each of my art school experiences was like that, and went on to inform my own teaching practice entirely.

What piece of advice would you give to your younger self?

By the time I’d left school I’d been pretty much inoculated against advice. But if I did meet my teenage self, I might attempt to remind him that feedback is essential and should be a constant feature of his practice. Feedback is the opposite of advice. You can think of it like driving a car. You’re getting feedback all the time — the sound of the road surface, the vibrations under the seat, the feel of the steering wheel, the pitch of the engine, a glimpse of a person crossing the road up ahead, a flash of something in a mirror, the sound of a siren behind you. Without this feedback you couldn’t progress. So as a creative, it’s your responsibility to distinguish between packets of feedback, to determine which need responding to, and which can be safely ignored.

What interesting thing about Cambridge might people not know?

It’s a beautiful city to look at, which is fine, but it’s the people who live and work there that are really interesting. They’re always getting up to something.

“People getting up to things is pretty much what Cambridge is all about. There is always a luxurious selection of concerts, film screenings, exhibitions, lectures, seminars, and workshops to go to, each of which will afford you an insight into another’s mind. Which, as a creative, you really need.”

Where now

ARU

BA (Hons) Graphic Design

With its vibrant studio culture, our Graphic Design degree will encourage you to push boundaries and challenge existing thinking by developing innovative design solutions as well as a keen understanding of professional practice.

Find out more

People

Idrees Rasouli

An award-winning designer of products, processes, and places, with a focus on disruptive market innovation, Idrees Rasouli is Associate Professor and Deputy Head of Cambridge School of Art.

Meet Idrees