Rachel Ryder

Staff. Historical Sociologist.

Rachel Ryder is a historical sociologist, and Course Leader / Senior Lecturer for the BA (Hons) Sociology at ARU.

The module she is best known for is 'Intoxicants and intoxication,' which takes in the broad field of alcohol studies, including production, consumption and distribution, globally and over time. It’s not just about alcohol addiction, which is the common assumption, but understanding the place of alcohol in society: who is using it and when, looking at aspects like gender, time, place, constructions of identity, culture, regulation, and criminal behaviour.

What one thing inspired you to do what you do now?

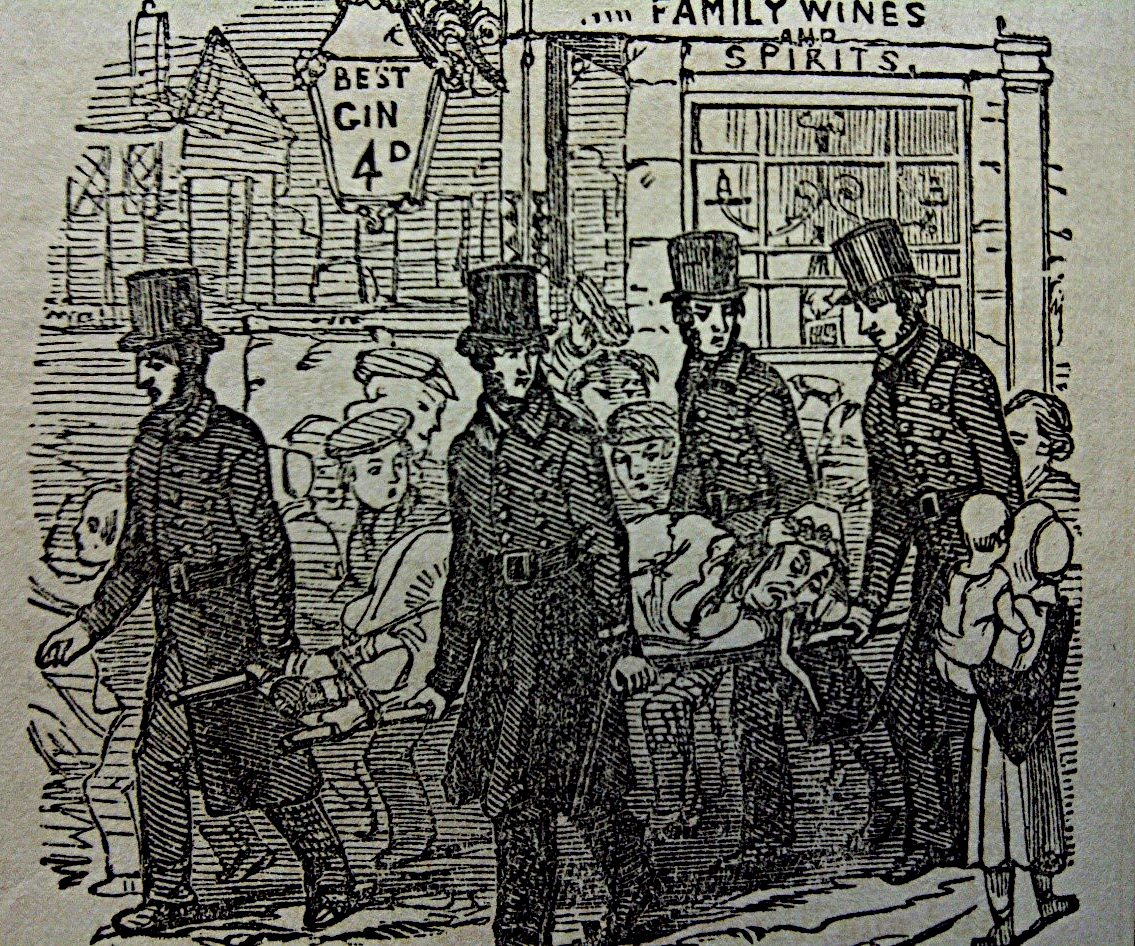

There were two things, in fact. The first was a particular image that inspired the entirety of my PhD. The Band of Hope, who were a temperance organisation for children, they published a newspaper called The Band of Hope Review. I found in one of them a postage-stamp sized illustration next to a little story about 2 women on Brick Lane who were carried away on stretchers by Police on Boxing Day 1850. The illustration had a strong resonance with a stock image that’s used in media, “Bench Girl,” - a woman sprawled back on a bench, legs sprawled open, with empty bottles all around her. In the alcohol studies field, this little illustration was her predecessor. Suddenly, I could see into the past, the construction of gender and alcohol as a social problem. It had always been there, but now it shone into view and told me something important about women’s drinking as a problem that had more to do with gender norms and how women should behave than it did about health. So that image inspired my research.

The second was more about gambling, which I ended up researching as an undergraduate, than alcohol. I’ve always been interested in people doing things that aren’t acceptable or socially desirable! In 2005, the gambling act completely changed the way bookmakers could present themselves. Before this, in small towns and cities, they were ubiquitous, one in every row of shops - strange and mysterious, with blocked out windows, smoke and odd noises pouring out whenever the door opened. It was only men that ever went in and out too - my grandad used to go, but it seemed completely obscure for me. Suddenly, after the Gambling act in 2005, the windows were all uncovered and you could see inside: the bright lighting, the fruit machines, the coffee machines were all a bit of a revelation. My fiancé at the time was heavily into betting too, so I was going into them for the first time and finally seeing inside. It was quite an enormous change so, as a sociologist, I was fascinated by the observability of them.

What piece of advice would you give to your younger self?

To talk to my tutors more. I tended to wander off and do my own thing when I was writing essays, and not take advantage of them being there. That’s probably where you learn the most when you’re gaining new skills.

What’s the most valuable thing you took away from education?

Research methods. It was the thing that got me my first job as a research assistant. Also just the recognition of how important it is to have skills, not just knowledges, and research is the key one that most organisations need.

How is emerging technology impacting on social research?

It’s huge. Absolutely huge. For example, I’ve got a 3rd year who is doing a dissertation on online fandoms and identity; norms around acceptable and polite forms of conduct. They’re part of the fandom of BTS - a KPOP band with a global online Twitter following, very politically engaged. In an ordinary year students doing surveys would hand them round to 10-15 people. With moving social research online, a student this year posted her survey to BTS fans on twitter and got over 100 responses in a few hours.

With modern technology, we’re able to create genuinely impactful research, but also have an immediate effect. We have digital archives. We can interview people all over the world. All the things that used to make research time consuming or expensive have gone, and public receptiveness to things like surveys has shot up too, because they’re always online. I can do real-time research into things that are going on right now, and also feed these things straight back into what I teach. Technology is making it all cheaper, faster, and easier.

What are you working on right now?

I’m currently supervising a doctoral student who’s doing a Vice Chancellor studentship about craft beer. It’s really interesting.

There was already a marked decline in beer sales pre-pandemic, but an amazing resilience in craft beer consumption, despite this. A lot of chain pubs are still designed around the relaunch of bars in late ‘90s - vertical bars, with cheap, strong alcohol. Generation Z were already drinking less anyway - they were more interested in event-based leisure like gigs and festivals, but less in going out on a Friday night just to drink alcohol.

Now, some craft beer businesses have actually grown during the pandemic, with consumers demonstrating a strong demand for locally produced beer. I do wonder if some pub chains will be able to get back the sort of custom they had previously.

That’s the thing about being a sociologist: you find yourself stepping into worlds you have very little knowledge about, then suddenly you’re engaged in detailed conversations about them. Sociology is about observing the world around you; trying to theorise, contextualise, and generally make sense of everything that’s going on.

Tell us something about Cambridge that other people might not know...

At the turn of 20th century, there were three temperance hotels in Cambridge, where the consumption of alcohol was not allowed. One was on market Hill, the Central Temperance Hotel; the Regent Hotel on Regent Street; and one on Mill Road, opposite the White Swan. Abstinence was a considerable marker of respectability for the lower middle class, and temperance travel was a big thing - Thomas Cook was originally a temperance travel company. Temperance was more far reaching and more pervasive in everyday life than we realise nowadays.

As an organisation, Temperance declined in the 1960s - but I think it’s been repackaged as well-being now. Its cultural resonances and the performance of outwards respectability continues in behaviours like extolling the virtues of ‘clean eating’, for example. It’s also strongly associated with products, a thread pulled on by contemporary organisations. You can even see it during the pandemic in the concern for staff well-being – it’s the same kind of management of workers for the purpose of keeping them highly productive and professional.

Where now

Our Favourite Places

Calverley's Brewery & Taproom

Calverley's Brewery is a beer lover's hidden gem, based just off Mill Road in the heart of Cambridge.

Find out more

People

Will Tullett

Teaching both the BA and MA History courses as well as supervising PhD students, Dr William Tullet focuses on the period from 16th century to early 20th, specialising in sensory history, with published works on smell, sound and emotions.

Meet Will

ARU

BA (Hons) Sociology

Delve beneath the surface of everyday life to understand modern societies, and specialise in areas such as cybercrime or social control.

Find out more