William Tullett

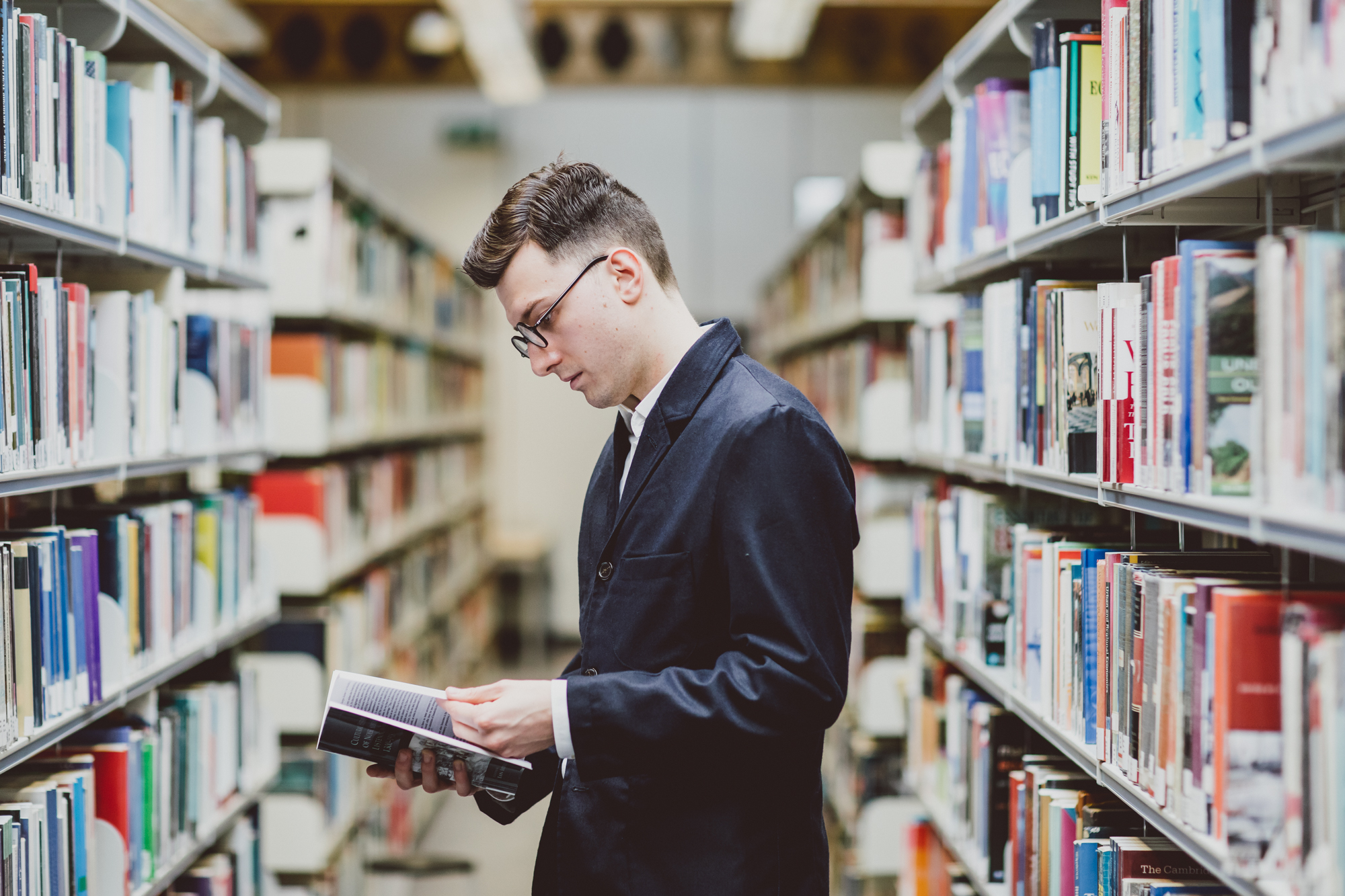

Staff. Historian

Teaching both the BA and MA History courses as well as supervising PhD students, Dr William Tullet focuses on the period from 16th century to early 20th, specialising in sensory history, with published works on smell, sound and emotions. William is currently working on a major EU funded project on the history of smell across Europe and its role in museums, heritage, and creative practice today.

What one thing (piece of art, writing, design, music, historical event etc) inspired you to do what you do now?

I’ve never been that interested in Kings and Queens or battles and wars. I’ve always been fascinated by the daily lives of ordinary and extraordinary people. The question I’m always asking in my teaching and research is: how did people in the past perceive the world around them – how did they see, smell, taste, touch, and listen to their worlds? We can never truly feel the past, but we can try and understand how it felt for the people that lived there.

For me, part of that involves trying to understand the incomprehensible and the bizarre by really getting to grips with a culture that is quite alien to us today. When I was a first-year undergraduate I read a piece of work by the historian David Sabean. It was about how a bunch of villagers in eighteenth-century Germany responded to a disease outbreak by burying a bull alive. This might seem a slightly odd – indeed cruel – way of dealing with disease. But to the villagers it made sense for all kinds of reasons that Sabean then goes on to explain.

What’s the most valuable thing you took away from education?

I think the most valuable thing I’ve take away education is two-fold. Firstly, a really critical attitude to everything I read and hear every day. I don’t mean this in a ‘well actually, I think you’ll find’ kind of way – I’m no QI-style pedant. What I mean is that my education has given me a curious, questioning, approach to the world. It has taught me to dig deeper rather than accepting things at face value.

Secondly, a desire to always understand other people’s points of view and their experiences. Sympathy and empathy are often in short supply in the contemporary world. But a willingness to understand things from another person or culture’s point of view – whether in the past or today – is crucial to making the world a better place. Understanding the past and present in order to make a better world for the future is really what universities are all about. That is what makes universities so valuable to society.

What piece of advice would you give to your younger self?

I’d probably tell my younger self to travel more. It’s only as I’ve become an academic and journeyed to conferences and archives across the world that I’ve really been able to travel beyond the UK. That has opened up all kinds of new experiences for me and I wish I’d had some of those earlier on my life. It’s one of those things that I think I kept putting off but, as the saying goes, there’s no time like the present. So my advice is that it’s always better to do things now rather than regret leaving them until later!

“Explaining how people made sense of their world is really what history is, for me, all about.”

What interesting thing about Cambridge might people not know?

The thing that people often forget about Cambridge is that it is so much more than a university town. Cambridge is a place with a rich history beyond its two universities. All of this is on show in the brilliant local history museums that we collaborate with in our research and teaching – such as the Museum of Cambridge and the Cambridge Museum of Technology.

Cambridge’s past ranges from controversial prisons for prostitutes (the ‘Spinning House’ which became a subject of national debate in the nineteenth century) to riots (such as the Garden House Riot of 1970 when protestors invaded a Cambridge hotel in a protest against the Greek government). These are the kinds of things we investigate with our first-year students. We get them in the archive straight away, within the first few weeks, and get them grappling with the documents that illuminate this rich and exciting local past.

Where now

ARU

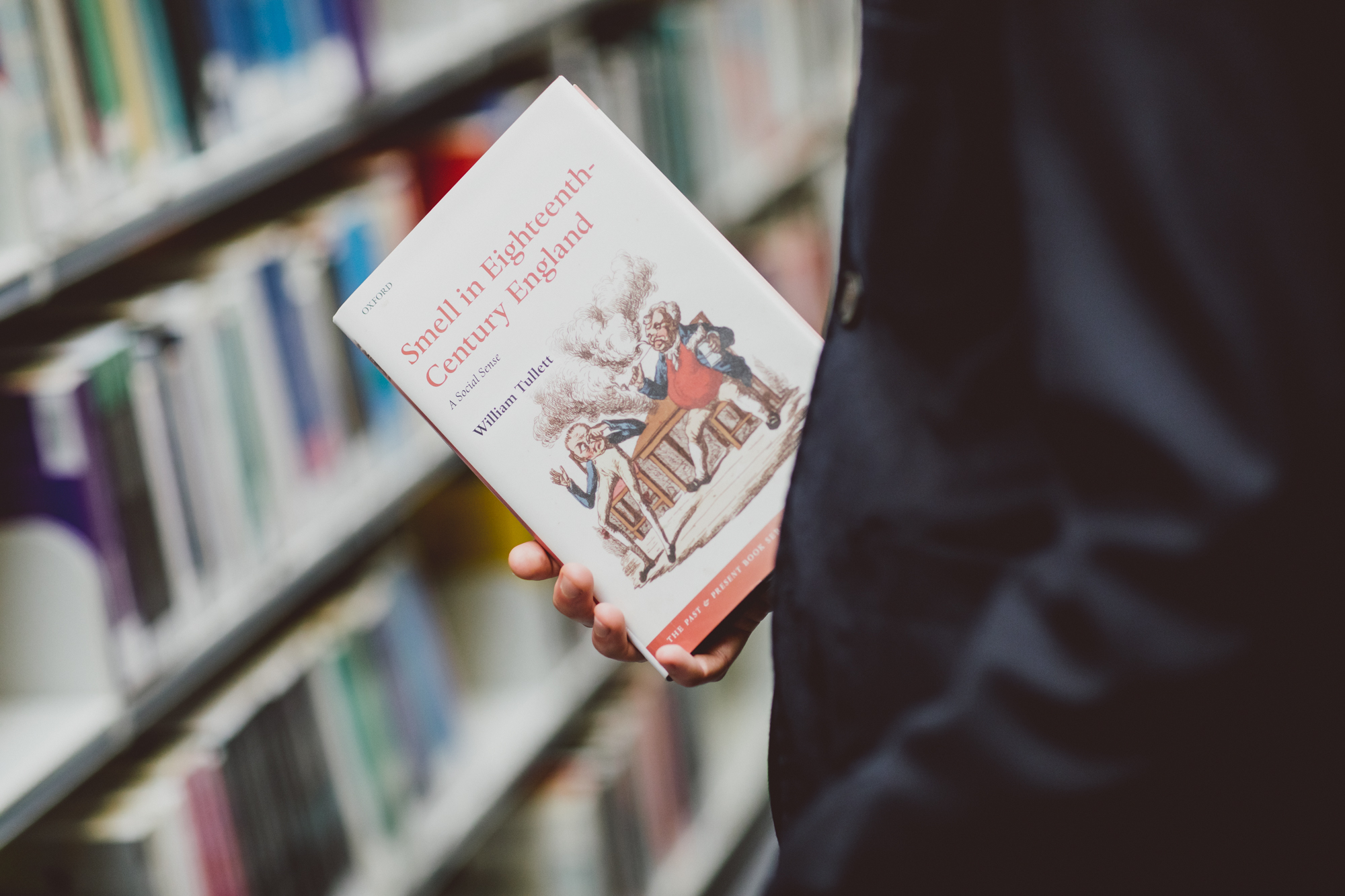

New project will rediscover our historic smells

Dr Will Tullett launches ambitious project to create a unique archive of European smells from the 16th to early 20th century.

See More

ARU

BA (Hons) History

Come face to face with the past, and explore what it can tell us about our present and future lives.

Find out more

People

Rachel Ryder

Rachel Ryder is a historical sociologist, and Course Leader / Senior Lecturer for the BA (Hons) Sociology at ARU.

Meet Rachel